President Peter Mutharika’s declaration that Malawi will no longer permit the export of unprocessed minerals has yet again set off a familiar national conversation. The announcement, delivered at Sanjika Palace in Blantyre during the swearing-in of new cabinet members, reflects a straightforward ambition: how can Malawi retain value within the country’s borders rather than exporting opportunity alongside raw materials? Yet beneath the surface of what looks like resource nationalism lies a web of practical questions about infrastructure, enforcement, and investor confidence which deserve a careful exploration. This article will attempt to do just that.

The Government’s Perspective: Capturing Value at Home

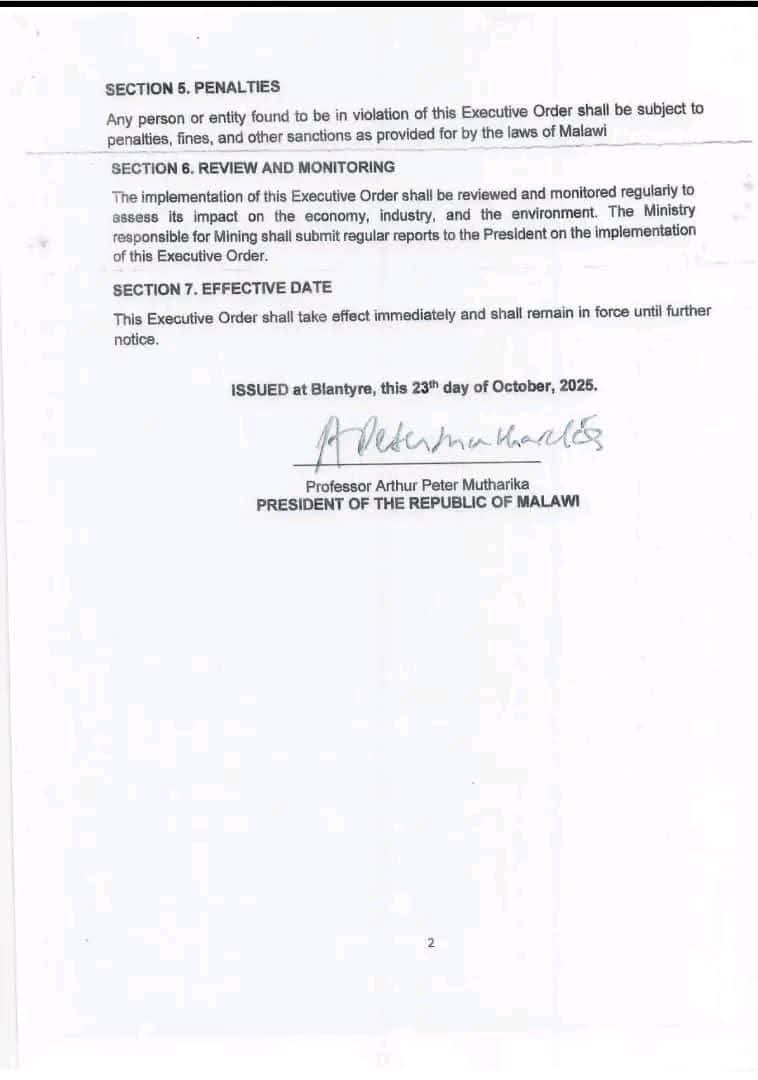

From the new government’s vantage point, the rationale embodied in the above executive order appears sound. I mean what’s wrong with prioritising local beneficiation to capture revenues that have long slipped away through unprocessed exports, while fostering job creation in sectors that employ thousands but so far delivers meager returns?

The calls for value-addition of everything from tea and coffee to mango products and nut products are indeed not new, as Malawians have been advocating for this holistic approach to resource sovereignty for years, echoing broader pan-African pushes against the “resource curse.” Remember the 2012 Malawi Economic Recovery Plan, in which President Joyce Banda explicitly called for increasing production alongside value addition and local processing of minerals to unlock their full economic potential and bolster foreign exchange earnings. That was 13 years ago, yet that vision, as urgent as it may be, remains unrealised.

So now, on the surface it looks like we finally have some meaningful executive push, which hopefully will be backed by enforceable policy.

This matters because when it is the case that Malawi sits on significant deposits that include rare earth elements at Kangankunde, rutile at Kasiya, graphite, uranium at Kayelekera, and gold in Mangochi, Lilongwe, Balaka, and Kasungu, that sounds like a lot of resources for a thriving processing sector. In fact Government officials estimate that these resources could generate upwards of $500 million annually if processed domestically. I must say I would like to see how they arrived at that figure, but let’s assume they’re within the ballpark range. For a country where mining currently contributes barely 1% to GDP, the potential transformation of such a bounty would be stratospheric, and cannot be overlooked.

The logic extends beyond mere revenue projections. Local processing would theoretically create employment throughout the value chain, from extraction through refining to export of finished products. The government has indicated plans to establish a National Mining Corporation to oversee this transition, ensuring transparency and accountability. Mutharika’s warning that “those involved in illegal mining or abuse, your days are numbered” suggests an accompanying intention to tighten regulatory oversight, although here too let’s take what’s been said with a pinch of salt. Because, as some readers will already know, in Malawi, intention doesn’t always translate to action. Even when an executive order has been fired out.

On another level, thr administration’s stance reflects frustration with a persistent pattern, which many Malawians are familiar with: Malawi exports raw materials at modest prices, only to import processed products derived from those same materials at considerably higher cost. And to add insult to injury, the exported product earns the national coffers next to nothing, meaning it’s virtually free to the exporter. This cycle, perpetuates dependency and limits industrial development. Thus, you’d hope that the ban represents an attempt to reverse decades of policy that prioritised extraction and export of raw materials over development of a processing ecosystem.

But where is the Infrastructure?

From the perspective of mining companies and investors, however, the announcement raises more questions than it answers. The most pressing concern centres on processing capacity. Malawi currently possesses no functioning large-scale refinery, no internationally accredited assay laboratory capable of verifying mineral quality and pricing, and no mineral exchange system. The infrastructure gap between policy declaration and practical implementation is… massive.

International mining firms face a calculation: invest significant capital in building processing facilities within Malawi, or redirect operations to jurisdictions with established infrastructure. The former requires confidence in regulatory stability, transparent licensing, and long-term policy consistency. The latter may mean closing up operations and leaving Malawi. Thus, some investors will see this sudden policy shift as a sign of instability, particularly when enforcement mechanisms remain undefined. Loopholes will be found.

The uncertainty compounds when considering the technical requirements. Different minerals demand different processing technologies. Rare earth element separation requires sophisticated chemical processes. Graphite beneficiation needs specialised equipment. Each mineral type presents distinct challenges, and few processing operations can achieve profitability without economies of scale. This means the investments required to even start any form of processing for some of the minerals is not only significant, but will take time. So, it’s likely that Investors will be seeking a reprieve or grace period in which they can continue to export raw materials (and earn an income from the resource) while starting to build the capacity for local processing. If such a grace period is offered, a monitoring regime will be required, to ensure that the construction of the processing facilities is realised. And doesn’t remain a verbal intention or merely a written promise.

What about Electricity?

Perhaps the most tangible obstacle facing any local processing ambition is Malawi’s electricity supply. The national grid currently generates approximately 554 megawatts, with peak demand already exceeding 350 megawatts and growing at roughly 6% annually. Hydropower accounts for the vast majority of generation, rendering the system vulnerable to climate variability. Recent years have witnessed recurring load-shedding and irregular power availability.

This is not good for processing operations, because mineral processing operations typically demand substantial, consistent electricity supplies. The Makanjira mining project, for instance, requires approximately 10 megawatts for full operation, yet grid connectivity to the area remains incomplete. The Kangankunde rare earth project faces similar challenges in that it requires 3 megawatts for its planned processing operations. Whilst this represents a relatively modest power requirement, it still necessitates grid connection infrastructure and backup generation capacity. Without reliable power, processing facilities cannot maintain the continuous operations that economic viability requires. This places additional burdens on investors that they also have to factor in on-premise electricity generation in their business plans – increasing the cost of the operation. This means, building processing facilities will inevitably increase the cost of electricity generation.

This problem isn’t only for investors to worry about.

Only a fraction of Malawians have access to electricity. Thus, in the absence of a large undertaking to increase additional generation capacity, the idea of diverting scarce power resources to industrial mineral processing, whilst understandable from an economic development perspective, presents difficult trade-offs. Never mind homes, what about the electricity requirements of local schools and hospitals many of whom are not currently connected to the national grid?

Plans exist to increase capacity, with government officials previously stating that 120 megawatts would be earmarked for mining projects. Whether this materialises, and on what timeline, remains uncertain.

The infrastructure isn’t ready

Beyond electricity, mineral processing demands supporting infrastructure: transport networks capable of moving heavy equipment and processed materials, water supplies for various refining processes, skilled technical personnel, and maintenance capacity for specialised machinery. Malawi’s industrial sector has historically focused on agricultural processing and import substitution manufacturing. Whichever way you look at it, the technical knowledge base for complex mineral refining is limited. So, maybe we should also immediately start technical studies on mineral processing at Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST) and other such institutions.

Transport infrastructure poses particular challenges for a landlocked nation. Road and rail connections to ports in Mozambique and Tanzania require maintenance and upgrading. Here, it’s important to note that while the Vale-funded railway known as the Nacala Logistics Corridor (NLC), connecting landlocked countries like Malawi and Zambia to the Port of Nacala in Mozambique is operational, the Nkaya-Mchinji railway which is an important feeder line that connects the Malawi-Zambia border and the capital, Lilongwe, to the main NLC junction at Nkaya, has been undergoing upgrades and rehabilitation to increase its capacity and efficiency for a few years now. So there already you have a problem.

This logistics factor matters because the costs of moving raw materials to processing sites, then transporting finished products to international markets, factor heavily into profitability calculations. Mining operations in remote areas like Makanjira village face additional logistical hurdles, especially considering the road network is not first rate.

So headlines aside, the absence of mature manufacturing infrastructure, and reliable road networks suggests that any transition to local processing should require a phased approach. Small-scale operations might prove feasible for certain minerals, particularly those already being extracted by artisanal miners. Large-scale processing facilities, however, would probably demand at least a year of infrastructure development before becoming operational.

Enforcement & monitoring Compliance

A ban achieves nothing if it cannot be enforced, and enforcement mechanisms remain conspicuously undefined. The so called “fines” in the executive order don’t mean much if they’re too little or cannot be enforced.

Further, Malawi’s borders, whilst not extensive, present numerous crossing points. The Ministry of Mining has acknowledged ongoing struggles with licensing fraud, unregistered artisanal miners, and outdated geological data. Declaring that minerals cannot leave the country unprocessed is one matter; preventing it is quite another. And the more resourced a mining entity is, the better prepared they will be with regards to certain things.

Malawi’s existing Mines and Minerals Act stipulates penalties for illegal mineral exports: individuals face fines of 10 million Malawian Kwacha plus double the value of illegally exported minerals, alongside two years’ imprisonment. Non-citizens face potential deportation. Corporate entities face 20 million Kwacha fines plus double the mineral value. Managers and directors may face personal imprisonment. On paper, these penalties appear substantial. In practice, enforcement depends on detection capacity, border control effectiveness, and judicial follow-through. Further, it’s currently not clear whether the stipulations of this executive order, fall under these provisions of the Act.

But Malawi’s experience with gold illustrates the challenge. President Lazarus Chakwera stated in 2020 that Malawi loses approximately $85 million worth of gold exports to the Middle East annually, with data from Gulf states confirming Malawi as a source of considerable gold volumes. This leakage occurs despite existing regulations. If current laws cannot prevent illegal gold exports, how will a broader ban on all raw mineral exports fare better? Shouldn’t we first try and tighten what we already have, and close the holes on the leakages we’re currently experiencing?

The Smuggling Risk: Lessons from the neighbours

African mining jurisdictions offer sobering precedents. Zimbabwe’s 2023 ban on raw lithium exports did not result in domestic processing expansion. Instead, smuggling networks flourished, moving lithium ore across the Mozambique border on back roads. Tanzania’s 2017 gold export ban similarly pushed miners towards illegal markets, draining government revenues whilst enforcement costs soared.

Nigeria’s experience with tin and gold export restrictions in the 2000s created smuggling syndicates that continue to control significant portions of trade today. The pattern proves consistent: when regulation outruns enforcement capacity, black markets expand. For Malawi, the danger is that artisanal and small-scale miners, who account for much of the country’s gold and gemstone extraction, will find themselves criminalised without viable alternatives.

These small-scale operators lack the capital to establish processing operations or access formal buyers who can handle unprocessed materials. They will likely turn to informal brokers operating beyond state oversight. Such transactions evade royalty payments and taxes whilst fostering corruption at border posts and within enforcement agencies. The irony would be palpable: a policy designed to capture value for Malawi, will instead end up bleeding the treasury whilst enriching smuggling networks.

What Penalties Will Actually Deter Violations?

Penalties mean little if violators calculate that the likelihood of detection and prosecution remains low. Malawi’s porous borders, stretched enforcement resources, and fragile institutional frameworks for mining regulation combine to create an environment where determined exporters might reasonably gamble on evading detection.

The existing penalty structure under the Mines and Minerals Act appears designed to deter through severity: imprisonment, deportation, and fines calculated as multiples of the illegal export value. Yet effectiveness depends not solely on penalty severity but on certainty of punishment. If violators perceive a low probability of being caught and prosecuted, even severe penalties lose deterrent effect.

Successful enforcement would require coordinated efforts across multiple agencies: mining inspectors to monitor extraction sites, border control officials to prevent smuggling, customs authorities to verify export documentation, and judicial systems to prosecute violations. Each represents a potential weak point. Corruption at any stage will undermine the entire framework.

What about a phased Implementation?

The thoughtful approach would treat the export ban not as an immediate decree but as an aspirational target tied to measurable infrastructure development. Processing facilities need to be built. Energy generation capacity must be expanded. Technical training programmes require putting in place. Regulatory systems demand strengthening. Border enforcement needs enhancement and oversight to prevent corruption. So, maybe let’s also set out a detailed timeline for all stakeholders, so that there’s a clear and predictable roadmap to the implementation.

Government should start by establishing clear phases: an initial period permitting raw exports whilst domestic processing capacity develops, followed by graduated restrictions tied to processing facility completion. Transparency about timelines and requirements would allow mining companies to plan investments accordingly. Interim measures might include export levies structured to encourage domestic processing whilst not completely prohibiting raw material exports until alternatives exist.

Such an approach acknowledges reality: infrastructure development if prioritised will take at least a year or more, and not months. Technical capacity also cannot be conjured overnight through declarations. You need living, breathing human beings to go to school and learn how to do each processing job. Shipping in whole factories and equipment into Malawi too, will take time.

Obviously the government knows that Investment decisions depend on regulatory certainty. Rushing implementation risks creating precisely the informal networks and smuggling operations that undermine both revenue collection and long-term sector development, as we’ve seen in other countries.

President Mutharika’s intentions appear commendable. So let’s give him credit for that. Yes, we all agree that the vision of Malawi capturing greater value from its mineral wealth resonates with legitimate aspirations for economic development, which have been around for decades. Yet dictats alone cannot substitute for the practical foundations that successful implementation demands.

Whether this ban ultimately drives industrial transformation or simply drives mineral exports underground will depend largely on whether the noble ambitions can be matched with pragmatic, phased execution that’s backed by substantial infrastructure investment. And only time will tell, which way the coin flips.

The coming months will reveal whether Mutharika’s government recognises these challenges and adapts its approach accordingly. Or whether patriotic declarations will yet again fail against the hard realities of enforcement capacity, electricity generation shortfalls, the unavailability of skilled staff, and the wide infrastructure gaps that exist. For a country seeking to leverage its mineral wealth towards prosperity, getting this balance right matters.