[The LONG READ]

Maybe there exists many other good ideas that would help citizens of poor countries get into employment, in particular creating jobs for young people. But the following is probably one of the better ones of such ideas.

Something quietly extraordinary happened in the 1990s and early 2000s that many of us barely registered at the time. Western companies, squeezed by shareholders demanding better margins and efficiency gains, started looking overseas for answers. And soon enough the phone call you made to complain about your internet connection, was answered in … Bangalore. The payroll processing for your company? That was handled in Dhaka. The software running your bank’s web application? Well, the most important bits of that were written in Hyderabad. Even the shirt on your back might have been stitched in Chittagong or in Colombo.

All this happened not only because countries like India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Vietnam just accepted this work. They grabbed it with both hands and ran with it. And so, what started as basic call centres and back-office data entry quickly evolved into sophisticated IT services, advanced manufacturing, complex logistics networks and eventually world-class companies that could compete anywhere. Tata Consultancy Services and Infosys became global IT powerhouses managing systems for Fortune 500 companies. Bangladeshi garment manufacturers now supply Marks & Spencer, H&M and Zara. Vietnamese electronics factories assemble Samsung phones and produce components for Apple. Filipino business process outsourcing firms handle customer service for half the world’s airlines and banks. Entire cities were utterly transformed in the space of a generation. A substantial middle class emerged where poverty had been the norm. Technical skills accumulated. National confidence followed.

Consider Infosys for example. The company was founded in 1981 with $250 borrowed from the founder’s wife. Now Infosys is worth over US$80 Billion and employs more than 300,000 people across dozens of countries. That’s the kind of transformation we’re talking about in that entire cities were utterly transformed in the space of a generation. A substantial middle class quickly emerged where poverty had been the norm. Technical skills accumulated.

But more importantly, National confidence followed.

None of this happened by chance or good fortune. These countries managed to align several important factors at exactly the right moment in history: available labour, improving education systems, reasonably supportive government policies, and foreign capital looking for opportunities.

The timing was everything.

Now, here’s the thing. The world appears to have moved into another one of those rare moments yet again. The question that should keep African leaders awake at night is whether they will recognise this opening in time, and do something about it. Or whether they will watch it pass by whilst caught up in the same tired and fruitless debates.

Capital Looking for Purpose, and Investors Looking for Meaning

You may already know this but two enormous shifts are happening right now. And they’re happening pretty much at the same time. When you look at them together, they create an opening that’s almost unprecedented.

The first is the largest generational wealth transfer in human history. We’re talking about trillions of pounds and dollars moving from older generations in Europe and North America to their children and grandchildren. See this article on Merrill Lynch. This isn’t money locked up in final salary pensions or the family home. Much of it is liquid, mobile, and actively looking for somewhere meaningful to go. The recipients of this wealth are often people in their thirties, forties and fifties who already have jobs, already own property, and are asking themselves what on earth they’re supposed to do with this windfall.

Now, many of them know what they are going to do with it, but quite a lot of them are not yet decided.

The second shift is the changing nature of work itself, particularly for educated professionals. Over the past few years, massive numbers of people have been laid off from technology companies, media organisations, consultancies and financial firms. These aren’t people without resources or options. Many have redundancy packages, savings accounts with anywhere from £25,000 to upwards of £200,000, solid professional networks, and years of experience. They’re educated, globally minded, they’ve traveled and have seen the world, and they’re cautious about pouring everything into stock markets that feel overheated or buying yet another buy-to-let flat in a market that might have peaked. And where property taxes eat into potential profits.

These people, often for the first time in their lives, are asking a very straightforward question: “What can I invest in that actually does something useful? Something real? Something that’s not another bubble. Something that will make a decent profit”

Many African countries have an answer to that question, whether their African governments and institutions realise it or not. Ofcourse some are actively working to attract investment, and have been encouraging viable vehicles for such investment. But others aren’t even scratching the surface.

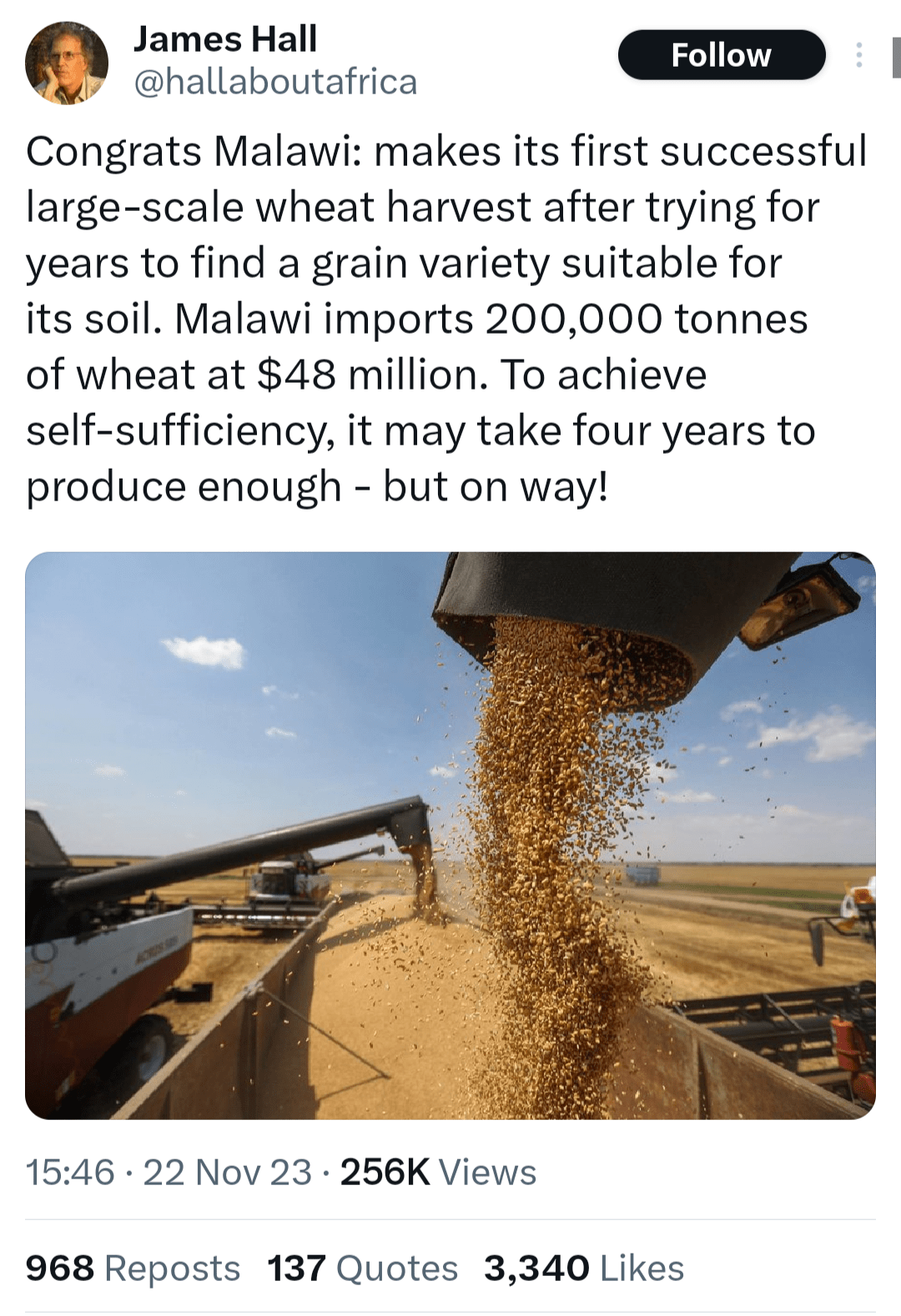

Malawi and the Case for the Real Economy

Let’s talk about Malawi specifically, the country of my birth, although this advice applies generally to dozens of countries across the continent.

Malawi, in my view, doesn’t need another complicated financial instrument dreamed up in a City of London boardroom. It doesn’t need more reports from international consultants or grand development theories that look impressive in PowerPoint but achieve little or nothing on the ground. I’ll be the first to tell you that.

What Malawi needs is quite simple: energy generation and distribution, factories and industry, processing plants, functioning logistics, skilled workers, and the ability to export goods that people actually want to buy. In other words, it needs its real economy to work harder and smarter.

And as this YouTuber and influencer will tell you, the industries that make the most sense aren’t always glamorous. Instead, they are often boring, but they’re proven. In Malawi’s context, we’re talking about Agro-processing of tea, coffee, groundnuts, soya and fruit that currently get exported raw at a fraction of their potential value. What about Fisheries, aquaculture and fish canning that could supply regional and international markets. Or food preservation and packaging that would reduce the shocking levels of post-harvest waste.We can even throw in animal feed production and manufacture here.

Similarly, Malawi needs light manufacturing of basic goods that are currently imported at great expense. There are textiles and garment assembly lines that are waiting to be built. In any case, wherever there are people, someone has to make clothes for them to wear. So the path that Bangladesh took, is very much already proven.

Renewable energy and energy services too present a massive opportunity, given the abundant sunshine and the desperate need for reliable power. Here, you can have a vertically integrated operation by ensuring that construction materials are produced locally rather than imported. This is profitable because it means you can also supply other sectors locally.

The final major industry that’s hungry for investment is Tourism-linked production and services that capture more of the value tourists bring. If you go anywhere near the lake, you ou can see signs of this industry everywhere. But it’s still in it’s infancy.

These aren’t sexy sectors that win innovation awards per se. But they employ thousands of people, have the potential to earn precious foreign currency, and can anchor entire communities around productive work.

In fact, if you think about it, you’ll find that almost every single country that has industrialised successfully started with these kinds of industries. This includes the wealthy nations that now lecture others about sustainable development whilst conveniently forgetting their own semi-primitive cottage industries in their histories.

Public-Private Partnerships with a Twist

So, if we were to make this concrete with a specific example, here’s what I think it would look like. Let’s imagine for a moment, a fish sourcing and canning company to be established in Malawi. I know, it’s not the sexiest example, but indulge me please.

The company is incorporated locally, under Malawian law, paying Malawian taxes. Its purpose is refreshingly straightforward. It sources fresh fish from local fishermen and fish farms, transports it efficiently using proper cold-chain logistics, processes and cans it in a modern facility. And finally, it sells the finished product both domestically and for export to regional markets. Nothing complicated.

The ownership structure can be designed deliberately, with national interests protected: 51 per cent is owned by the Government of Malawi, ensuring the country maintains control and the company’s interests align with national development goals over the long term. 49 per cent is opened to private investors, both local and international, who are carefully vetted and subject to ownership caps to prevent any single investor dominating the company. But the company would be managed privately, and thete would not be any direct links to the government.

This structure alone makes good sense because it means unlike other “investment” undertakings common across Africa, such an ownership structure makes it possible for the country to have a real chance of raising resources with which to spend on healthcare, education and social services. And before you scoff about how possible it is for a fish processing company to earn enough to pay for a hospital or a school in a poor part of Malawi, Maruha Nichiro Corporation, based in Tokyo, Japan, is the world’s largest seafood and fish processing company by revenue. For the fiscal year ending March 2023, the company reported sales exceeding ¥1 trillion (approximately USD 7 billion/EUR 6.4 billion). So, fis(or seafood in general), can earn a few bucks.

But what makes this model I’m proposing here unique is how the initial capital and public attention are raised.

Soft Power Meets Factory Floors

Instead of the usual dreary donor conference in a Geneva hotel or a slick investor roadshow targeting pension funds, the launch is built around a high-profile, tightly managed media and fundraising event that’s relevant for the TikTok and Instagram age.

A small, carefully selected group of internationally recognised celebrities and influencers would be invited to participate. These aren’t random names pulled from a magazine. Instead, they’re chosen for their established track record of serious charitable or social engagement, and for the care they’ve shown for peoples of the world. Think people like Angelina Jolie, Miley Cyrus, Halle Berry and Usain Bolt.

But why these particular people? Well, for one, their involvement would actually mean something. Angelina Jolie for example has spent decades working on refugee issues with the UN. She has funded education projects in conflict zones, and has advocated relentlessly for women’s rights globally. Her involvement signals seriousness. Miley Cyrus founded the Happy Hippie Foundation, which focuses on youth homelessness, LGBTQ+ rights and mental health support. She’s demonstrated genuine commitment beyond social media posts, and her inclusion would greatly energise the initiative. Then we have Halle Berry, who has supported diabetes awareness, domestic violence prevention and children’s causes through both financial contributions and personal advocacy, over many years. These are notable women who have spent decades supporting and pushing serious issues. Finally, but of no less importance is Usain Bolt. Everyone knows him. Bolt has invested heavily in education and sports development in Jamaica, funding schools and youth programmes with his own money, not just lending his name. And so, his involvement would also be invaluable to the initiative.

But there are many other famous faces doing amazing things that can be called upon.

Here, it must be made clear that the event is framed not as a celebrity endorsement or a charity appeal, but as active participation in a practical effort to create jobs and build industry in a small African country. The message is clear: this is investment with impact, not a handout.

How it would work – the details

Picture this, a sunny day in Salima, by Lake Malawi. The entire filming takes place in a single, carefully planned day. This respects everyone’s schedules and keeps costs firmly contained.

Four short video pieces are produced, with all the celebrities appearing in each of them, each highlighting a different aspect of the project: the fishing communities, the processing facility, the export potential, the tourism appeal, and the wider economic impact, etc.

The total celebrity remuneration is £200,000, or £50,000 each. This is well below their usual rates for commercial work, reflecting the social purpose of the project. And crucially, payment is contractually structured to come from funds raised during the event itself, not paid upfront from development budgets. But their travel arrangements would need to be organised, and paid for upfront.

In addition, the planning can be made so that production and logistics costs are kept intentionally modest without compromising on professionalism. This means a central location that’s accessible. Salima is just about an hour’s drive from Lilongwe, Malawi’s capital. And one can fly to Lilongwe from London, Nairobi or Johannesburg.

You would then need a medium-sized but highly capable advertising agency handling creative direction, as well as a lean filming crew. Think experienced videographers who know how to work efficiently; professional costume and makeup artists to ensure everyone looks good on camera; security staff who can manage crowds and protect participants discreetly; and event cabins and basic hospitality that create a professional atmosphere without extravagance.

The total production and event cost can be capped at £250,000, bringing the overall budget to £450,000. This is remarkably lean for an event of this profile and potential impact.

Sponsors, Investors and the Press

To fund the event, six sponsorship slots would be sold at £80,000 each before the event filming. Sponsors aren’t just writing cheques and walking away. Instead, they would receive meaningful brand exposure, access to the filming location, opportunities for photographs with the celebrities, and carefully managed press visibility. Each sponsoring party would be able to bring 4 guests to the event. They would be able to observe the filming from a dedicated viewing area, with proper catering and light entertainment provided. For companies looking to demonstrate corporate social responsibility beyond the usual greenwashing, this is genuine engagement.

The press strategy is absolutely central to making this model work. Major international media outlets would be specifically invited and given real access. Dedicated interview cabins would be set up for 30-minute one-on-one interviews with the participating celebrities.

Media organisations like The New York Times, the BBC, The Guardian, or leading European outlets would be charged around £10,000 per interview slot. Here’s the clever bit: the majority of this fee goes directly to the development cause rather than disappearing into administrative overheads. The media get exclusive content with major personalities. The celebrities get a platform to speak about issues they genuinely care about, from refugee crises in Sudan, and education access, to mental health and youth empowerment – in a neutral environment. And the project gets funding plus massive international visibility.

This isn’t just a photo-shoot. It’s a platform where serious conversations can happen whilst cameras are rolling.

A professional media manager and a number of junior associates would need to be employed specifically to coordinate interviews, manage the flow of journalists, and ensure messaging remains coherent throughout. A trained security team would ensure the event runs safely and smoothly without feeling oppressive. Even the local police would be invited…

What about Everyday Investors?

So, if GoM owns 51% of the undertaking, here’s what we would do with the remaining 49 per cent of the company, and the terms on which investment would be accepted. What if we offered it to private investors through a structure designed to be accessible but controlled: for example, individual shares could be sold in 0.5 per cent units at £15,000 each. And the maximum ownership per individual capped at 7 per cent, to allow a broader participation by various investors. Thus, the maximum individual investment would therefore be £210,000.

With such a structure, the target capital raised would be is roughly £1.4 million, which is sufficient to establish a modern processing facility, purchase equipment, employ staff and provide working capital.

Investors would also have the option to attend the launch event, observe the proceedings, and meet the celebrities if they wish. This isn’t necessary for returns, but it humanises the investment and builds genuine trust. People invest in things they can see and touch, not just spreadsheets.

The event itself is promoted not as a glamorous party but as a nation-building exercise that leverages the power of celebrity to bring into focus issues of employment creation, export development and skills transfer. The charitable angle is there, but it’s grounded in economic reality, and sustainability.

Profit with a Conscience

When people say its impossible to reduce poverty in Africa, I laugh. Because I’ve seen other countries do just that, and do it extremely well. And it seems those who speak like this forget of the examples of Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, even the likes of Vietnam…if we set aside the Chinese example for a moment.

It’s not that African countries can’t reduce poverty levels. It’s that Africa doesn’t receive the right kind of resources channeled to the right things, by the right people, to have the right kind of impact.

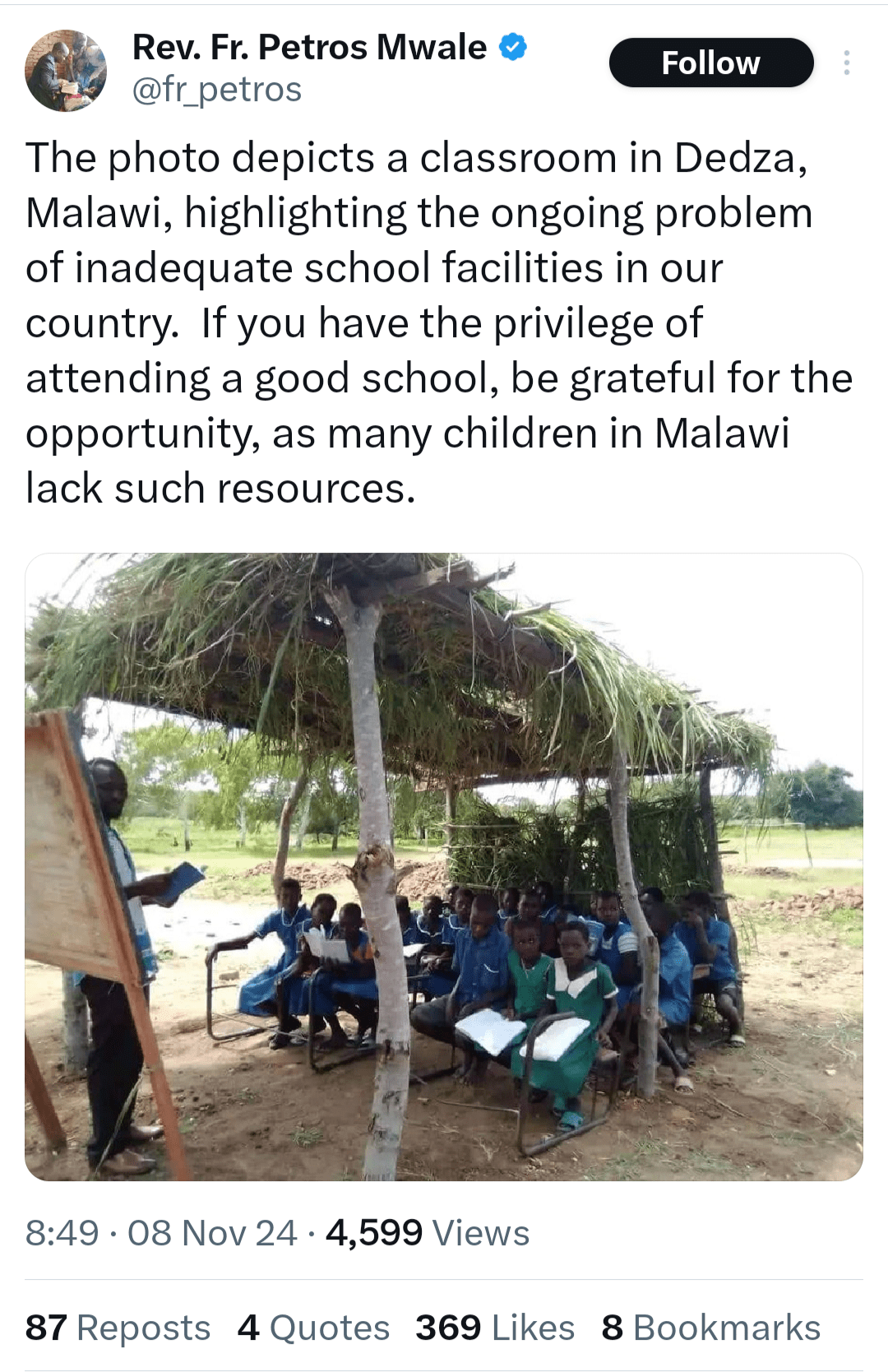

Thus, to ensure the company remains anchored in local communities rather than becoming just another extractive enterprise, a commitment could be made so that 5 percent of net profits are committed to a community development fund.

This would earmark and support projects such as local schools and vocational training programmes (which in Malawi are severely underfunded, but would create the next generation of skilled workers). It would support healthcare initiatives in fishing communities (that often lack basic medical services). It would buy and donate safety equipment for fishermen, reducing death rates. And more broadly, it would help in infrastructure improvements that benefit the wider community, not just the company making the investment. This is important because in most parts of Malawi, the infrastructure is still quite under-developed. So, here’s how you could fund Youth Employment Programmes that create pathways into the formal economy.

This isn’t charity bolted on as an afterthought when profits are good. It’s built into the corporate DNA from day one, written into the company’s articles of association.

Imagination Goes a Long Way

Malawi and countries like it across Africa have often been held back not only by politics and corruption, but by a profound shortage of imagination. Development has too often been something that happens in consultant reports and donor conferences rather than in factories and on shop floors. It’s been about what international organisations think poor countries need, rather than what those countries can actually build and sell.

Asia’s outsourcing boom shows exactly what becomes possible when timing meets intention, when governments create space for enterprise, and when international capital finds attractive returns in emerging markets. It shows that when the stars are aligned, and countries seized the moment, great things can happen.

Today’s generational wealth transfer and the upheaval in professional labour markets present another such opening. It might not come around again for another 20 or 30 years.

So, what if well-structured partnerships that protect national interests, present investment opportunities which prevents exploitation, make good use of smart media to create genuine visibility, and a healthy dose of creativity, even small economies can punch well above their weight.

Malawi has just 20 million people. But 20 million people who have not been served well by successive governments spanning over 50+ years. Still, it’s 20 million consumers who comprise a market. A market where such type of industry as is being proposed here, when scaled up, can export far beyond those borders. And create sustainability.

So, if a few globally recognised celebrities eating locally caught fish on camera can make something amazing happen, why not?

The question is whether anyone in Lilongwe or any other African capital is bold enough to try something different.

//Article Thumbnail Rights: Lake Malawi, Mangochi, Ismail Mia via Flickr//